Abstract

CASE STUDY

THA is a 40-year-old immigrant from Myanmar who has been living in the United States for about 6 years. He has a history of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection for many years, for which he has never received any treatment. He is negative for hepatitis B ‘e’ antigen (HBeAG), with normal liver enzymes on his routine primary care visits.

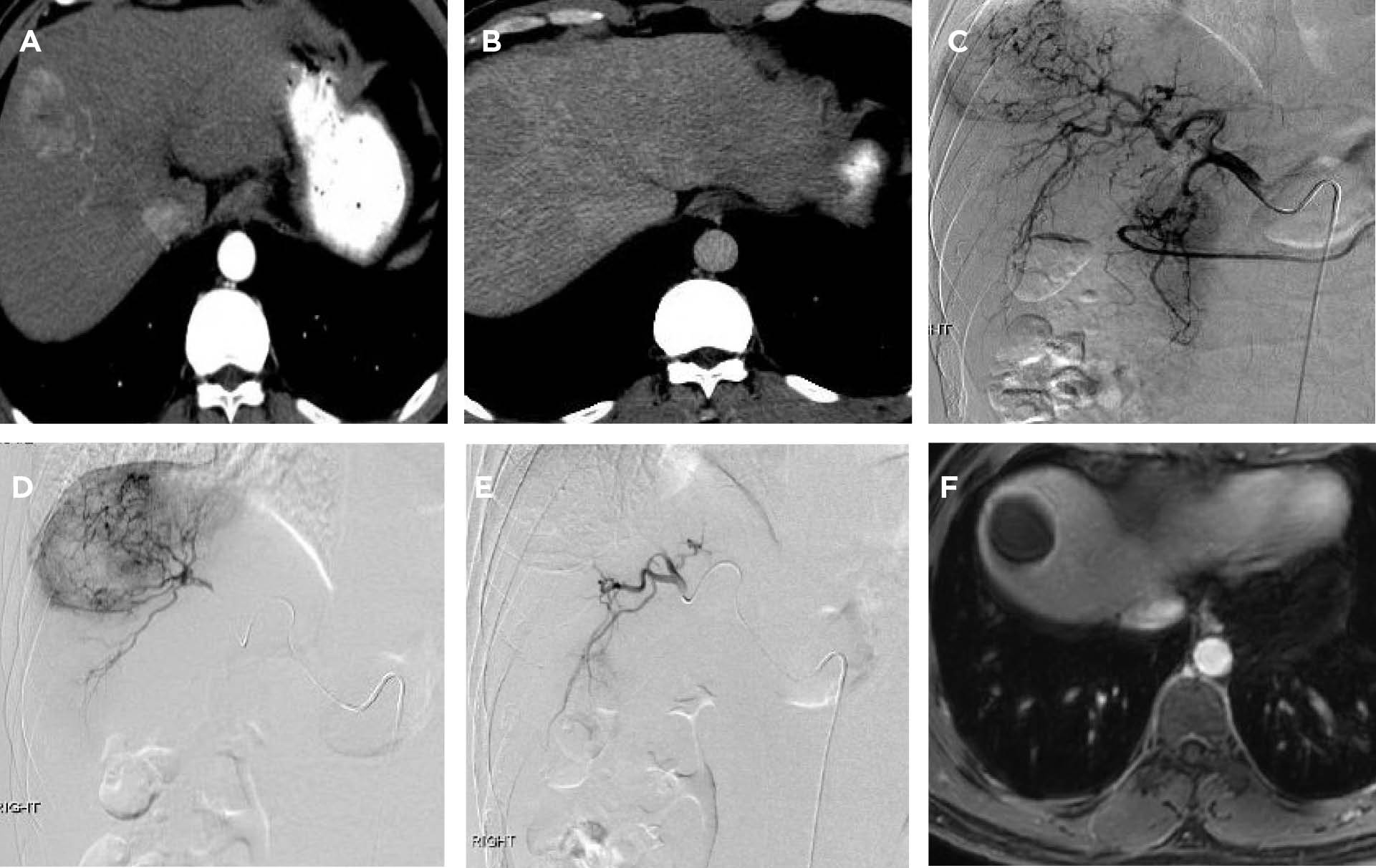

THA was referred to a hepatology clinic when recent laboratory studies revealed a slowly increasing tumor marker—alpha-fetoprotein level (AFP). His AFP increased from a normal level of 8 ng/mL (normal range, 0–8 ng/mL) in December 2014 to 44 ng/mL in June 2015. His HBV DNA level was 30,409 IU/mL. Because of his history of chronic hepatitis B infection and the rising AFP level, a computed tomography (CT) scan was done and showed a 4 cm x 3.5 cm liver mass in segment 8, accompanied by cirrhotic morphology to the liver (see Figures 1A–1D on page 765).

As THA has no other medical problems and remains active in his community and at home, he was referred to a liver cancer treatment program for consideration of liver transplantation, which could be an effective cure. THA is classified as Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) A (early disease, single tumor) with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, Child-Turcotte-Pugh A cirrhosis.

THA was determined to be a good candidate for transplant, based on the BCLC and Milan criteria (Forner, Reig, de Lope, & Bruix, 2010; Mazzaferro et al., 1996). The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 22 for hepatocellular carcinoma, based on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN)/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) guidelines (which are followed by our institution, University of Michigan Health System, for liver allocation). His tumor met the size criteria for a good outcome after transplant, and he had the necessary social support, as transplantation is a lifelong event requiring both social and psychological adjustment.

THA was then referred to interventional radiology for consideration of locoregional liver-directed therapies. This would offer disease control and stability while he underwent the additional testing necessary before being placed on the transplant list. After a patient is formally placed on the list for transplant, there is at least a 6-month wait to receive a liver due to the organ allocation process and medical necessity. Bridging liver-directed therapies protect a patient’s candidacy for curative transplant and may help to decrease the dropout rate from the transplant waiting list, thereby having a positive effect on posttransplant survival and tumor recurrence rates (Graziadei et al., 2003; National Comprehensive Cancer Network

[NCCN], 2015).

During his transarterial chemoembolization procedure, THA underwent an arteriogram, which revealed the solitary hypervascular mass in the right lobe. Selective transarterial chemoembolization was then done by injecting 1 vial of 100 to 300 µm drug-eluting LC Bead particles loaded with 75 mg of doxorubicin into the target artery supplying the tumor. A postembolization arteriogram showed no residual tumor blush (see Figure 1E below).

THA experienced mild nausea and several days of minimal fatigue. He recovered well, with no residual effects. A follow-up magnetic resonance imaging performed 6 weeks after his procedure revealed greater than 95% tumor response (see Figure 1F below). THA now will undergo imaging every 6 weeks until he receives a transplant.